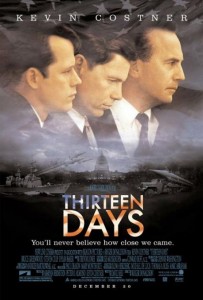

When I first watched Thirteen Days, I was shocked how close the Cuban Missile Crisis brought us to armageddon. I’m old enough to remember the end of the Cold War, but the hair’s breadth from conflict that the film portrays is eye opening.

The film dramatises the traumatic period in 1962 from when American spy planes identify Russian missiles in Cuba, to the successful resolution of the crisis two long weeks later. As in Apollo 13, you know the outcome, but it’s a taut and gripping film nonetheless.

From a leadership perspective, it’s a fascinating study of a young and still relatively inexperienced President John F Kennedy, played by Bruce Greenwood, and his trusted inner circle – brother Bobby (Stephen Culp) and Special Adviser Kenny O’Donnell (Kevin Costner). Under pressure from jingoistic military advisers, the President has to balance national security and political concerns with the horror of possible nuclear war.

Acutely aware of the potential impact of following standard protocol and joining the Russians in an uncompromising stance where neither gives in, the President has to seek a ‘third way’ which avoids conflict while safeguarding his country’s security and political power.

It’s a great film for role modelling ‘challenging the process’, with the President and his inner circle frequently having to challenge established military thinking and his advisers’ uninformed or stereotypical views of the Russians. In one scene, Bobby Kennedy bangs the table of the Security Council meeting, refusing to accept an air strike on Cuba is the only possible action. His personal, heartfelt appeal to Secretary of Defence McNamara eventually elicits a grudging concession that a naval blockade may also be a possibility.

The parallels for business are clear. While the situation may be less precipitous, it’s easy to become constrained by a narrow view of reality rather than opening up to new possibilities or markets – one reason why many businesses fail to move with the times.

Thirteen Days is really a study of how a leader and his team confront a crisis: how they organise resources, involve the right people, make things happen and, perhaps most importantly, stay strong and focused in the face of huge pressure both from inside and outside the organisation.

In one lovely scene, O’Donnell takes his flustered President to one side before he appears on live television to brief his country on the crisis. He pours him a drink, chats about old times, and tells him a story to reinforce the faith O’Donnell has in his Commander in Chief. It calms the President down, and helps steel him for the challenge ahead. You could argue that O’Donnell is both encouraging the heart and enabling others to act – and he’s successful at both.