Imagine you’re in a meeting with 11 of your peers. They are all in agreement and keen to move on. You are the only one to have doubts, but the stakes are extraordinarily high: a man’s life. What do you do?

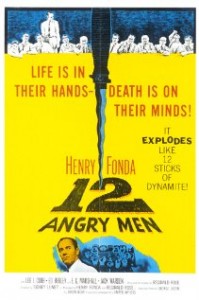

That’s the premise of Sidney Lumet’s 1957 film 12 Angry Men, a fascinating study of influence and leadership.

As the jury of a murder trial retire to consider their verdict, Henry Fonda’s Juror 8 is the lone dissenting voice who refuses to sanction a unanimous guilty verdict. Though uncertain of the defendant’s guilt or innocence, his insistence on re-examining the case gradually leads the remaining 11 jurors to change their minds.

12 Angry Men is a classic illustration of Kouzes and Posner’s leadership behaviour Challenge the Process. It is the hottest day of the year, everyone is keen to escape the stifling jury room, and Juror 8’s stand leaves him ridiculed and unpopular.

Seeking to challenge the accepted view, he enlists a number of influencing techniques to support him.

1. Ask, don’t tell

Juror 8 is able to sow seeds of doubt in the minds of his colleagues simply by asking challenging questions. He identifies flaws in the prosecution’s case and in the commitment of the defence team, but lets his fellow jurors come to their own conclusions about their meaning.

2. Deal

To gain early agreement to further discussion, Juror 8 proposes a deal: if a secret ballot finds at least two jurors in favour of acquittal, they’ll discuss the case further. If not, he’ll accept the majority view. The gamble pays off, with the elderly juror changing his vote and the remaining jurors committed to their part of the deal.

3. Build alliances

It’s not easy being the lone dissenter – but that doesn’t mean you’re wrong. At the start, Juror 8 needs just one person to support his request to discuss the case further. Gradually, others are persuaded by his arguments, and the momentum builds as they re-examine their own niggling doubts and identify further loopholes.

4. Make your case visual and compelling

John Kotter rightly argues that getting people to feel (as opposed to think) differently is most effective at changing behaviour. He suggests creating surprising, compelling and preferably visual experiences for that purpose. Juror 8 illustrates this in the scene below by dramatically throwing a duplicate knife on the table to prove the ubiquity of the apparently ‘unique’ murder weapon.

5. Use others’ expertise

Juror 8 uses the expert testimony of fellow jurors whose personal experience lends authenticity to his argument: the elderly juror who can understand the motivations of a key witness; the man who lived near the elevated subway; the juror who’d witnessed knife fights.

6. Identify the hidden agenda

Our experience and preconceptions all contribute to our view of the world. Juror 8 skilfully exposes his colleagues’ hidden motivations, revealing them both to themselves and to each other. One juror’s enthusiasm to convict is laid bare as a deep-rooted prejudice based on fear: another’s is rooted in the failure of his relationship with his own son.

This last technique has an associated lesson for leaders. How often do we allow our own preconceptions to go unchecked? Constantly re-examining the reasons for our own views and opinions can lead to far better decisions.