Why are performance reviews often so ineffective? And why can simply omitting someone from your email distribution list generate a strong emotional response?

Recent developments in neuroscience can throw light on these questions. The invention of fMRI (functional magnetic resonance imaging) machines now allows scientists to see which parts of the brain are activated under different conditions.

This means we can better understand how our brains work. It allows us to understand not just why we may be feeling the way we do, but why our family, friends and colleagues feel the way they do too.

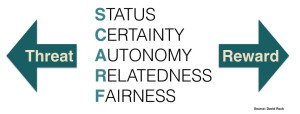

The SCARF model

David Rock’s SCARF model (pdf download) summarises some of the key learnings from neuroscience in relation to human behaviour, and presents it in a easily digestible format.

The model is based on a simple premise: that just like our ancient ancestors, we assess all new information with a view to either:

- approaching it – where we see it has potential for reward, or

- avoiding it – where we believe it presents a threat

The SCARF model highlights the key social triggers that can generate this ‘approach or avoid’ response. Let’s look at each trigger and how teacher Erin Gruwell makes them work for her class in the movie Freedom Writers.

Status

Status is about our relative position in a community or society. We all have a perception of our own relative status. Activities like recognition from a boss, or winning in sports can boost that sense of status.

But even small threats to our sense of status can generate a threat response. That’s why being excluded – even from an email list – can feel like an assault on your status. I once came across a senior manager who objected to his name being the last of many on an email distribution list. To him, that was a threat to his status.

Performance reviews, according to Rock, are often ineffective because of the status threat they provoke. One way to avoid that, he suggests, is to encourage individuals to give themselves feedback on their performance.

In Freedom Writers, Erin’s students are initially treated as third-class citizens by the section head and the other teachers, many of whom have given up on them. Their status is rock bottom. Erin generates an approach response by buying them brand new books – which she funds by taking on a second job – and taking them on school outings. Suddenly, they feel a boost in their status, and respond accordingly.

Certainty

Our brains crave an element of certainty and stability, as constant uncertainty makes them work harder and expend more energy.

That’s why organisational change programmes, or relationships where you’re unsure of the other person’s expectations or feelings, can be hugely stressful. The uncertainty of these situations generates a threat response.

The majority of Erin’s class in Freedom Writers lead difficult lives, blighted by violence, homelessness and family strife. Erin creates a safe and stable classroom environment, one where they can escape their chaotic personal lives and feel supported and understood. You can see the effect this has on one student in the clip below.

Autonomy

Autonomy is a sense of control of your environment, and authors like Dan Pink have identified its central role to motivation. When you feel a lack of autonomy – when being micromanaged, for example – your brain can produce a strong threat response.

Erin gives her students a journal for them to write in each day. But she gives them complete autonomy over the task. They can write on any subject they want. And if they don’t want to, that’s fine too.

But they do – in droves. The task allows her students to express themselves, and gives them complete control over how and when they do it. It’s an outlet for them to feel more in control of their lives.

Relatedness

Relatedness involves deciding whether others are ‘in’ or ‘out’ of a social group: whether someone is friend or foe. We all have a need for safe human contact, and in its absence the body generates a threat response.

As humans, we have a tendency to form ‘tribes’ where we can have that safe and rewarding human contact – whether through family, friends, work colleagues, sports teams or social clubs.

In the clip below, Erin’s ‘line game’ overcomes her students’ distrust and aggression towards each other, helping them to see they’re more alike than they realise.

Fairness

Many studies show that fairness is a bigger driver than outright reward. For example, social experiments show that people would rather receive a smaller monetary reward if they perceive it to be fair, than a higher monetary reward they perceive to be unfair in relation to what other people receive.

Perceptions of unfairness can generate powerful threat responses: in extreme circumstances, leading to civil unrest or even revolution.

In Freedom Writers, Erin treats all her class the same – regardless of their background, personality or behaviour. She wants to support each one of them in becoming the best they can be.

It sends a powerful message – one her class moves towards, rather than away from.