Who’d have thought that ‘Management by Walking Around’ (MBWA) was actually ‘invented’ by US President Abraham Lincoln?

MBWA reputedly originated at Hewlett Packard in the 1970s, and was brought to wider attention by management consultants like Tom Peters.

But according to historian Stephen Oates, it really started when Lincoln began informally inspecting Union Army troops during the American Civil War.

Management by Walking Around involves leaders visiting workplaces to chat to employees and uncover any issues. Whilst the term seems less widely used today, the concept is still practised by many leaders.

Former Royal Mail Chairman Allan Leighton, for example, would often turn up unannounced at operational sites to chat to employees. In his book On Leadership, he reveals his aim of uncovering the ‘real picture’ of frontline issues, rather than the ‘sanitised’ version sometimes presented by middle managers.

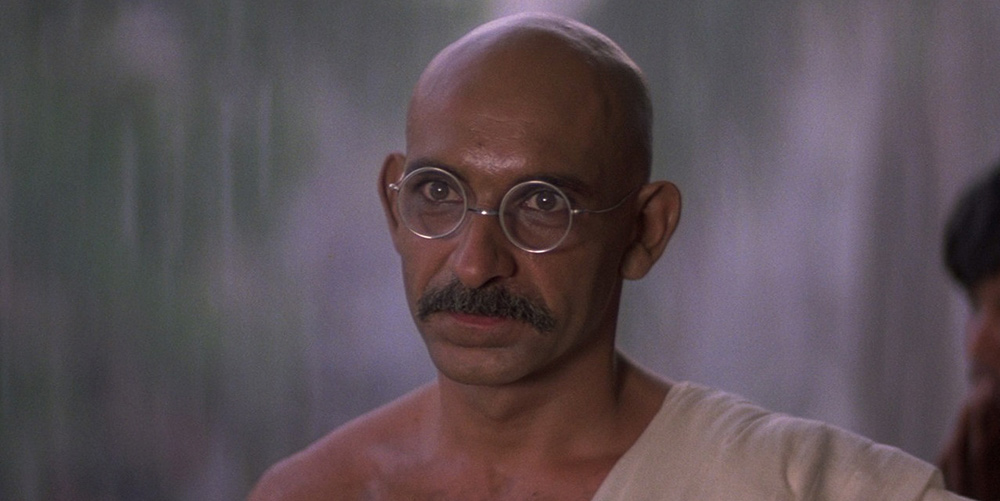

In Lincoln, you can see the President using this technique, both on a battlefield visit and on trips to see wounded soldiers in hospital.

In an article in Fortune magazine, executive coach Annie Stevens proposes six tips to make MBWA work effectively. Let’s see how Lincoln demonstrates them.

1. Make MBWA part of your routine

Creating a fixed schedule for walking around will ruin the informality – but if you don’t allocate it regular diary time then other priorities will get in the way.

When Lincoln visits wounded soldiers, it’s clear this isn’t an isolated gesture – he recognises one of the troops from a previous visit. He’s prioritised the importance of visiting and spending time with frontline troops, despite the heavy time demands of his role.

2. Don’t bring an entourage

Bringing aides or assistants, Stevens notes, may inhibit open discussion. In the opening battlefield scene in Lincoln, the President sits in an open tent, bodyguards at a discrete distance, and with no other aides present. It makes him appear open and approachable.

3. Visit everybody

Dropping in on some colleagues more often than others will definitely send the wrong message. In the opening scene, Lincoln makes himself available to everyone equally, allowing anyone who has questions or comments to come and see him, regardless of their rank or colour.

He also demonstrates an inclusive approach. In the hospital scene, for example, he makes a point of shaking each soldier’s hand and asking their name.

4. Ask for suggestions, and recognise good ideas

Stevens suggests leaders ask employees for thoughts and suggestions on how to improve the business.

Whilst the President doesn’t ask for ideas, he does ask questions. He commends his black troops on their bravery in a recent battle. He takes an interest in his troops and their lives.

Lincoln also demonstrates another powerful use of MBWA – checking recall and understanding of recent communications. The ‘communication’ in question here is famous for its brevity – the Gettysburg address. Lincoln asks the soldiers what they remember of it. He’s rewarded when, between them, they can recite it word for word.

5. Follow up with answers

If you can’t answer an employee’s question immediately, Stevens advises, get back to him or her with an answer later. This builds trust.

Lincoln isn’t asked any questions in these scenes, but his willingness to listen and openness to feedback both engender trust.

6. Don’t criticize

The main purpose of MBWA is to find out what’s happening ‘at the coal face’. Inevitably, some of the feedback will be negative. And while it may be tempting to respond immediately or be defensive, doing so is counterproductive.

In the battlefield scene, Lincoln is challenged by Corporal Clark on the inequity of black soldiers’ rights. He acknowledges Clark’s views but doesn’t become annoyed or defensive. Instead, he defuses the agitated corporal with good-natured humour. When one of the white soldiers asks an impertinent question, Lincoln simply ignores it and asks a question of his own. When they leave, he thanks them all and wishes them all the best.

MBWA may take time and effort, but it can yield excellent results.

And perhaps we’ve got Lincoln to thank for starting it all off.